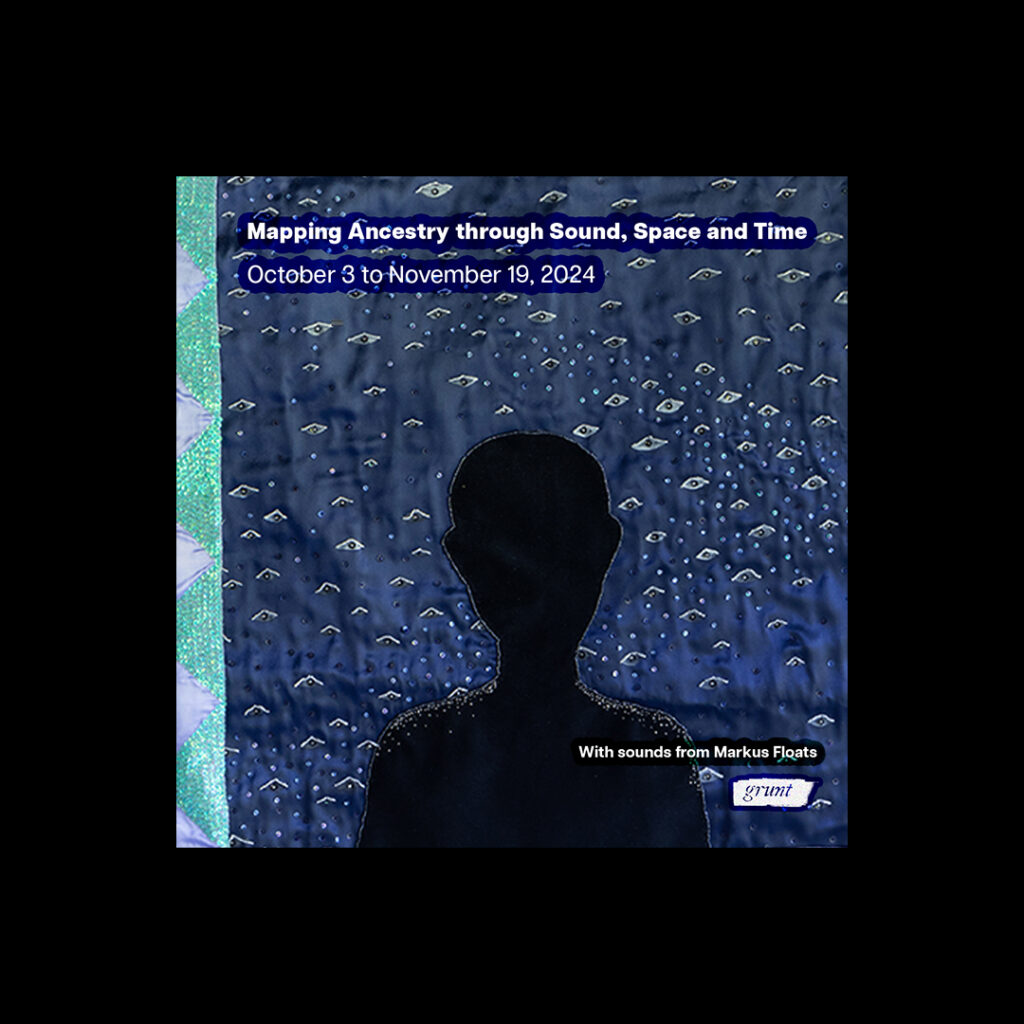

In this exhibition, Mapping Ancestry through Sound, Space and Time, artist Stina Baudin animates her Haitian ancestry through research and reconstructed stories around cultural emblems, knowledge, time and land. Baudin’s previous work has drawn from statistical examinations of Black time and migration, visualized as large textured weavings; in this exhibition she focuses the depth of her time in the creation of her own versions of ‘Drapo Vodou’ (known in English as Vodou Flags). Baudin positions colonial time as an ideology that, “as the structural backbone of slavery, dominating cultural norms, informed by race-making and capital, dictated how time should be used”. Colonial time imposed on Black and Indigenous lands becomes a weapon, disrupting not only the rhythms and rituals related to traditional ways of being, but also long established relationality with the land and its usage.

The works in this exhibition are a project of revolutionary artifacts; Drapo Vodou is linked to both the sacred world as well as the Haitian Revolution (1791 – 1804). Drapo Vodou played a significant role in the revolution, like Black American quilts, they carried hidden encoded messages and connected communities in resistance. The act of creating these works for Baudin acknowledges the difficulty in gathering lost familial knowledge as generations continue; “our past is a feat that isn’t always accessible by conversation, returns to our native lands or through extensive pre-existing archives. The documents and ledgers of our stories are fragmented versions of tales I am constantly attempting to piece back together through my fibre and multidisciplinary work.”

Baudin’s exhibition includes soundscapes in collaboration with Montréal/Tiotia’ke-based sound artist, musician and composer Markus Floats, whose live performances include accompaniment by specific sampling or reading from Black literary canon, with a focus on exploring themes of repetition, obscurity, and visibility. Join us for Markus’ performance at 7:30 PM opening night, followed by a talk-back session with Stina.

Stina Baudin’s Website: https://stinabaudin.com/

Stina Baudin’s Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/ssteenaa/

Markus Floats Bandcamp: https://markusfloats.bandcamp.com/music

Markus Floats Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/markus.floats

Digitized Programming:

Virtual Walkthrough:

We captured a 360 of the exhibition, but only have the rights to share 5 active shows at a time. Here are stills that were pulled from the 360. If you would like to experience our 360 capture of Mapping Ancestry…, please contact archives@grunt.ca

Description: The video is a silent pan through the show starting at the welcome station facing south, and panning left before it flies up and shows the gallery as a “dollhouse” from above before coming back down and panning the show looking south and panning right.

Images courtesy of Stina Baudin and Savannah Faith Jackson.

Reflections on Pursuing Decolonial Time

Written by Curator, Whess Harman.

Mapping Ancestry Through Sound, Space and Time moves through ideas of decolonial time; a thing I know and crave but am often instinctively outside of. There is no one fixed definition of exactly what decolonial time is, despite the enthusiasm the phrase inspires. More often than not for myself, “decolonial time” and my particular brand of “ndn time”, is often the admission of having been railroaded into conceding to and compromising for what is more and more pervasively present colonial measure of time: a thing that is linear, definitive, tracked, monolithic, production driven, institutionally mediated, violently enforced and always hungry to eat into the social and leisure time where relationships are built. This runs contrary to the ideals of decolonial time; social time and deep time that is not scrutinized, that languishes and rolls in and through the day and conversations; unhurried and urgent moments alike where unexpected connection can bubble up when everyone’s guard is relaxed or the trust exists to fumble through together. This time is often wedged between periods of vexations in colonial time: I didn’t send that email. I didn’t submit that writing. The work is not done. I failed to make my time measurably productive.

We had ambitions in the early stages of this exhibition; there were hopes of doing a book club. We applied for funding to offer a weaving workshop to other Black community members. There was talk of a vessel for offerings, a place to deposit some of the complicated, fractalling grief that can be felt within and around us to bring some order through ritualizing it. These things were not possible despite our best efforts and now live in the dissolving edges of “imagine if” and “if only”.

For many artists I’ve worked with in the past few years, this tenuousness between putting up an exhibition, which should be something a little bit serious but a lot celebratory, has been difficult to mediate against deadlines and schedules lost in the uncertain deluge of overwhelming grief against seemingly unstoppable and inexplicably cruel acts of violence being enacted not only in Palestine, but also still in liberated Haiti, in the Congo, Sudan and decolonial struggle across the globe. Match that with the pressure to make everything mean something, to connect it all, or be thoughtful enough to speak to all parts of a question–creating art becomes a tremendous thing to ask. Atop it all? “Be professional” even if the human thing you want to do, the only thing that helps in some moments, is to scream and cry at the top of your lungs. The reassurance I’ve had in facing this collection of ambitions and expectations that are both external and internalized is remembering that this whole thing we’re going through is collective, global and distinctly colonial. We, colonized and displaced peoples across the globe, did not make these circumstances for ourselves. So our meetings will have miscommunications, some awkward moments and crying and we’ll still hold onto what matters; the dreaming.

Stina held onto the dreaming; her dedicated and deep work shines through in the craftsmanship of these pieces. The voodoo flags in this exhibition feel timely as they are derived from a lineage of revolutionary work that comes from her Haitian ancestry. She describes the flags as similarly aligned to the history of resistance within Black quilting practices, used to subversively carry messages that could be transmitted beyond the periphery of the colonial eye for libratory and revolutionary purpose. The Haitian Revolution, a rebellion lasting twelve years between 1791 and 1804, is often cited as the only successful slave rebellion in recorded history. There’s power in that. There’s lineage in that. There’s also nostalgia in it–while organizing against colonial tyranny has become more globalized online, we lack the tactile remnants of radical transmissions produced in the domicile. These works feel both an ode and a call to honor the practices that came before, while reflecting how the image of “productivity” was used to obscure crucial tactical messaging; a Black body sewing is not outwardly the same threat as the resistance it’s messaging to. It has not been a small piece of the work for Stina to think through the formation of the Black body as a resource for colonial extraction both historically and contemporaneously.

With this work, I am reminded of a series of workshops created by Syrus Marcus Ware, where he reframed art-builds for protests and demonstrations instead as an event titled, “In Movement: Training Sessions for Freedom Fighters”. This was done to address that when advertised as an art build, the greatest response repeatedly came from racialized queer and femme folks in our communities. This project pointed to the time-consuming and invisibilized labour often namelessly used to aestheticize movements as being deserving of examination and respect. And too, a valuable space to build community. While there have not been names found in Stina’s growing knowledge of this moment of voodoo flags, the labour of those ancestors is at least honoured in this exhibition and her making was in communion with them. If the images we use matter, so do the hands that make them. I think of this in relation to the collaborative sound works produced by Markus Floats; in these works are embedded the voices of Black thinkers and writers who have shaped the work of both Markus and Stina. Again; there is a power here that is beyond colonial imagining, and a lineage.

I haven’t defined succinctly what decolonial time is or how it can operate in an institution (in my opinion, echoes of it can and reformation will still not centre it) and neither can this exhibition. But the work can speak toward some of the finer qualities of decolonial time. Perhaps primarily that it is non-linear. If it’s a 12 year rebellion, 500 years of resistance or over 75 years of occupation, decolonial time speaks beyond deadlines, last chances and last ditch efforts. Decolonial time holds the past, present and future together; we work while in solidarity and conversation with those behind and those ahead and look at every site of our lives as a potential for resistance. I met Stina in a time of many parallel struggles and we were not perfect. But, we persisted, adding this exhibition to the chorus of our ambitious revolutions.

![Bold white sans-serif font outlined in a dark red-brown promotes Mariana’s artist talk with details of date, time, and location included in the caption of this post. At the very bottom is smaller text reading, “Presented with support from the” above a series of white logos including the Aboriginal Gathering Place, grunt gallery, the Manitoba Arts Council and Canada Council for the Arts. The background is an orange wall brightly lit in a gallery space with a worn wood floor and white trim. On the gallery floor at bottom, are single Tyndall stones located at left, and right. They appear to have a warm beige colour. On the orange wall background at the right of centre frame, is a square image featuring a wall made up of dark grey stones with leafy plants including a pink flower There is a red-brown brick floor in the image’s background. This photo of Mariana Muñoz Gomez’s work was taken by Darren Rigo.]](https://grunt.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/SLIDE06-819x1024.jpg)