Glenn Alteen, grunt’s founder, curator and program director, has been awarded the Governor General’s Outstanding Contribution Award. (more…)

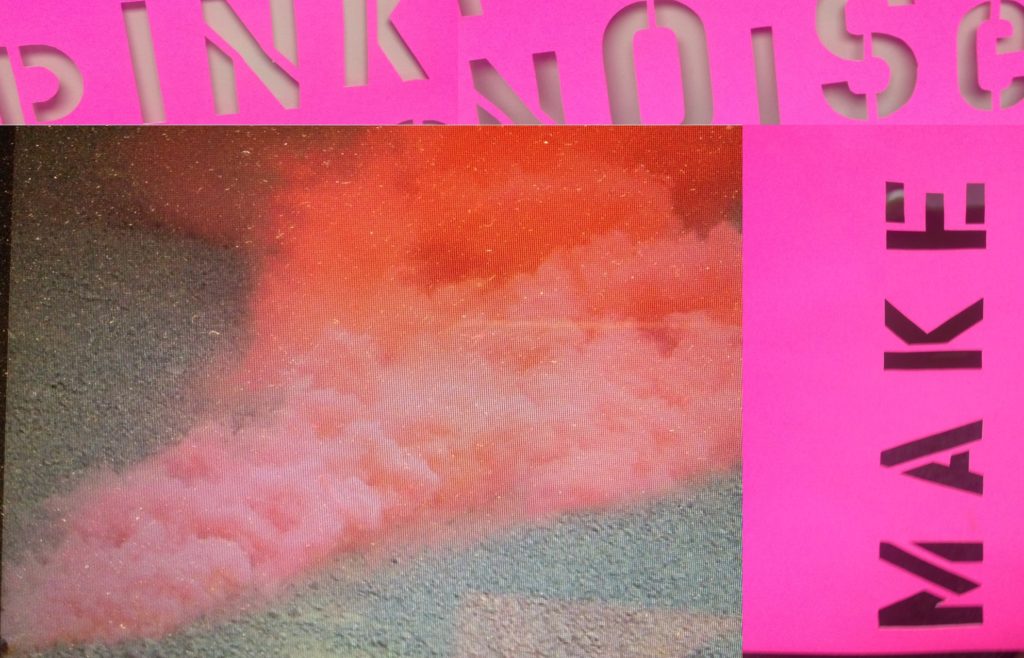

Azadeh Emadi: Motion Within Motion

Video Still from Motion Within Motion (2017)

Exhibition: May 2 – 12, 2018

Opening Reception

- Date/Time: Tuesday, May 1, 2018, 7– 9 PM

- Location: grunt gallery #116 350 – East 2nd Ave

Artist Talk: Azadeh Emadi

- Date/Time: Thursday, May 10, 2018, 6 – 7 PM

- Location: grunt gallery #116 350 – East 2nd Ave

Lecture:“Creative Algorithms: From Islamic Art to Digital Media”, Dr Laura U. Marks

- Date/Time: Wednesday, May 23, 2018, 7– 9 PM

- Location: SFU Harbour Centre, Rm 7000

Azadeh Emadi – Motion Within Motion

grunt gallery, in conjunction with SFU School for Contemporary Arts and Centre for Comparative Muslim Studies, presents the first Canadian exhibition by Glasgow-based artist Azadeh Emadi.

Motion Within Motion, a two-channel video installation with immersive sound, is inspired by Persian-Islamic philosophy of change. Using the theory of ‘substantial motion’ (al-harakat al-jawhariyya) by philosopher Mulla Sadrā Shirazi (1571-1641) as a starting point, Emadi employs digital video and installation technologies to challenge human-centric assumptions of change, time and motion. The work engages two distinct points of view: a non-narrative documentary filmed in Iran and an altered variation that magnifies the footage to the pixel-level. The resulting installation is both synchronized and perceptually disjointed, demanding a simultaneous reading of both cinematic time/movement and the largely abstracted constituent parts of the digital image. Zooming in and out of focus, splitting images into units and using different modalities of time and motion, Emadi’s installation reveals the inner activities of the frame – and provides experience “from a pixel’s point of view.”

Motion Within Motion will be presented in the Main Gallery, and is accompanied by Floating Tiles, a related work in the Media Lab. Floating Tiles continues the artist’s exploration of time and perception via the juxtaposition of classical Islamic tilework – themselves the product of algorithmic pattern creation – and the digital manipulation of the pixel.

The exhibition corresponds with Dr. Emadi’s research residency with Dr. Laura U. Marks at SFU’s School for the Contemporary Arts until early June 2018.

Programs include an artist talk and conversation with Dr. Marks on May 10th at the gallery, and a special presentation of Dr. Marks’ popular lecture “Creative Algorithms: From Islamic Art to Digital Media” on May 23rd at SFU Harbour Centre, Room 7000.

Biography:

Azadeh Emadi is a video maker and media artist who experiments with alternative approaches to image making process and technologies of perception. In applying and developing aspects of classical Persian-Islamic culture and concepts, her work aims to stimulate dialogue between Western and Middle Eastern cultures. Her videos and installations explore the intersection between reality, perception, technology and time, as an investigation for finding new ways of seeing that innovatively address some of the current socio-cultural and environmental issues. She is also a lecturer and researcher at the School of Culture and Creative Arts (Film and Television Studies Department), The University of Glasgow.

Pink Noise Pop Up

“Pink noise” is a specialized frequency with a specific relationship to human biorhythms that is said to increase focus and productivity. This concept provides the aesthetic criteria and an instigator for interaction in Pink Noise Pop Up—a research project initiated by Instant Coffee that embraces colour and sound as conduits for emotional connection.

grunt gallery presents the upcoming exhibition by Instant Coffee with four Canadian artists showing in South Korea for the first time: Jeneen Frei Njootli, Krista Belle Stewart, Ron Tran and Casey Wei. Installations and performances by Korean artists will also be featured. Pink Noise Pop Up is curated by Vanessa Kwan (Curator of grunt gallery) and Inyoung Yeo (Director of Space One)

Pink Noise Pop Up will unfold simultaneously at Space One, an artist-run center, and ONE AND J. Gallery +1, a commercial space for emerging artists. Working within the context of both mainstream and alternative sites (in addition to the neighourhoods they occupy), the exhibition combines the aesthetics of consumer display with the improvisational play of social interaction.

Check back here for updates on Pink Noise Pop Up.

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Province of British Columbia.

The Making of an Archive

Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn’s The Making of an Archive is a project that seeks to collect images of everyday life photographed by Canadian immigrants, in a direct, collective and exploratory approach.

The Making of an Archive

Book Launch and Artist Talk with Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn

A collaboration with grunt gallery

Thursday, June 21, 2018 at 5 PM

In collaboration with grunt gallery and in conjunction with the opening reception for Beginning with the Seventies: Radial Change, the Belkin is pleased to present a book launch and artist talk with Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn. The main catalyst for the initiation of Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn’s project The Making of an Archive was the photo albums of the artist’s father, an amateur photographer who took countless photographs of his daily life when he first immigrated to Canada in the 1970s. However, while doing research for previous works, the lack of representation of the immigrant’s daily life in state narratives seemed paradoxical for a country that is internationally known as the instigator of multiculturalism. Due to this visual deficiency and threat of photographic disintegration, Nguyễn initiated The Making of an Archive, a project that seeks to collect images of everyday life photographed by migrants, particularly of people of colour, in a direct, collective and exploratory approach. One of the salient themes of the work is how to make visible the rich histories of activism and solidarity that complicate the pervasive myth of the agreeable “model minority.” The publication The Making of an Archive serves as a critical document of Nguyễn’s research and the project’s relevance to larger conversations around Canadian vernacular photography by people of colour, the role of the artist-initiated archive, and how an expansion of the archival record relates to political and social change. As part of the book launch, the artist will ask, what is the process of building a collective archive and how do we come to understand our own pictures, together?

Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn is a research-based artist and uses a broad range of media, often relying on archival material to investigate issues of historicity, collectivity, Utopian politics and multiculturalism within the framework of feminist theory. Currently based in Stockholm, she completed the Whitney’s Independent Study Program, New York, in 2011, having obtained her MFA and a post-graduate diploma in Critical Studies from the Malmö Art Academy, Sweden, in 2005, and a BFA from Concordia University, Montreal, in 2003. Nguyễn’s work has been shown internationally in institutions including SAVVY, Berlin (2017); EFA Project Space, New York (2016); Mercer Union, Toronto (2015); MTL BNL at the Musée d’Art Contemporain, Montreal (2014); Kunstverein Braunschweig, Germany (2013); Apexart, New York (2013); and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia (2011). She has also been awarded a number of grants for her research-based practice from the Canada Council for the Arts; The Banff Centre’s Brenda and Jamie Mackie Fellowship for Visual Artists; and The Swedish Arts Grants Committee’s International Program for Visual Arts. Nguyễn was the 2017 Audain Visual Artist In Residence at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver and participated in the fourth cycle of NTU Center for Contemporary Art Singapore’s Residencies Program. In 2018, Nguyễn was nominated as one of the five finalists for the third MNBAQ Contemporary Art Award by The Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec.

The Making of an Archive is edited by Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn, grunt gallery’s Curator Vanessa Kwan and Archives Manager Dan Pon, with contributions by Liz Park, Gabrielle Moser, Fatima Jaffer, Dan Pon and Tara Robertson, Maiko Tanaka and an introduction by Vanessa Kwan. The publication is designed by Chris Lee.

—

For more information go to the Belkin Gallery

The Making of an Archive book will be available in our online book store soon.

—

For further information please contact: Jana Tyner at jana.tyner@ubc.ca,

tel: (604) 822-1389, or fax: (604) 822-6689

Nuova Icona Director, Dr Vittorio Urbani, in conversation with Director Glenn Alteen

Glenn Alteen, Director of grunt gallery, in conversation with Vittorio Urbani, Nuova Icona Director. The talk will take place at the Italian Cultural Centre on Tuesday, October 17 at 7 pm. (more…)

2017 Annual General Meeting

Leave a commentBlue Cabin Artist Talk

Leave a commentGRUNT SUPPORTS _______.

Leave a commentThe Making of an Archive: FAQ

Are you or your family an immigrant to Canada? Are you interested in being a part of a growing archive of community history? Do you have family photos you would like to digitize? Please consider taking part in The Making of an Archive, a project initiated by artist Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn and presented by grunt gallery (Vancouver) and Gendai Gallery (Toronto).

What

We are inviting contribution of photographs (slides or prints) of your family’s experience of immigration in Canada. We are most interested in personal collections – those images that taken within families and communities by friends/relatives with personal connections to the subjects.

How

The archives at grunt gallery are equipped with digitization and storage capabilities, and we are inviting members of the public (you!) to bring photographs (prints, 35mm, Polaroids, slides or negatives) We give you a digital copy of the images and store a copy in The Making of an Archive collection. The originals are returned to you.

What will happen to my images?

Jacqueline is keeping a repository of this growing archive, and grunt will be maintaining a back up of any images collected via our onsite sessions. The images may at some point be featured online or in print – but only with your written permission.

Some questions that might help:

What images, for you, show how your family + community supported one another?

(This is a very open question – many collections include bbqs, social gatherings, birthday parties, special dinners and so on; all this is relevant!)

Do you have images that show your family engaging publicly with events/ organizing/ volunteering?

(We have gathered some amazing images of people at community meetings, cultural festivals, marches and protests – this is the kind of thing that is really lacking in official archives.)

Are there images outside the scope of the archives?

Studio photography in its stale fashion (think of Sears portrait photography!) is not so much relevant to us. We are interested in life with its struggles, joys, friendships, strangeness and hope.

How many images can I bring?

We will digitize collections from 1 – 100 images (that’s 1 – 2 photo books, generally).

What time commitment is required?

Up to 2 hours, depending on the size of your collection. We collect the images beforehand, digitize them, and then invite you to sit with our volunteers for a short interview while we review the material – where you describe to us what is happening in the images. We record and keep this oral account of the images as part of the archive.

Where can I learn more?

Online:

Via grunt’s website: https://grunt.ca/the-making-of-an-archive/

Via the Making of an Archive Website: https://www.themakingofanarchive.com/ (currently under construction)

Image courtesy Tatsuo Kage